AI, Misinformation and the Ballot: A Digital Challenge for the 13th National Election

Campaigning for Bangladesh’s 13th National Parliamentary Election officially begins on January 22. Although printed posters have been banned this time, electioneering is gaining momentum in multidimensional forms across digital platforms. In this context, the Election Commission (EC) has identified “information distortion in cyberspace” as a major challenge. Throughout the month, concerns have been raised over the spread of AI-generated and fake videos and images, alongside repeated references to the need for stricter legal measures to address the issue.

Continuing this narrative, EC Secretary Akhtar Ahmed has said that counting votes in the upcoming election will require some additional time due to the inclusion of party-symbol ballots, referendum ballots, and postal ballots. He urged the media to play a responsible role so that no misinformation or rumors spread over the extended vote-counting process.

He made the call at a high-level meeting on overall law and order held on Wednesday, January 21, ahead of both the 13th parliamentary election and the referendum on the implementation of the July National Charter. The meeting, held at the Chief Adviser’s Office in Tejgaon, was chaired by Chief Adviser of the interim government, Professor Muhammad Yunus.

Later in the afternoon, at a press briefing at the Foreign Service Academy, Chief Adviser’s Press Secretary Shafiqul Alam elaborated on the matter. He said that voter numbers vary from center to center, and that alongside vote counting, referendum votes will also be counted this time. As a result, the publication of election results may be delayed in some areas.

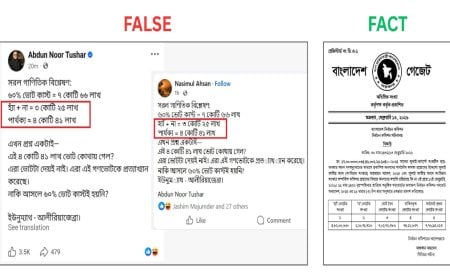

Meanwhile, even as election vehicles have begun moving, the digital space has already been flooded with various forms of disinformation. AI-generated content is being used to show members of law enforcement urging votes for specific parties. Artificially created female and religious minority characters are also being used to criticize rival parties. According to observations by fact-checking organization Dismislab, one out of every three pieces of disinformation circulated in 2025 was AI-generated. Statistics from another fact-checking platform, Rumor Scanner, indicate that 309 instances of false information related to the parliamentary election had spread on social media up to last December. Overall, 2,281 cases of political disinformation were identified over the past year—more than in any other category. Additionally, data from the International Panel on the Information Environment (IPIE) election database shows that AI was used in four out of five elections held globally in 2024.

Despite such alarming trends, although the Representation of the People Order (RPO) prohibits the creation, publication, dissemination, and sharing of false, misleading, biased, hateful, obscene, indecent, or defamatory content using artificial intelligence, no strict enforcement measures have been observed so far. Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) A M M Nasir Uddin had earlier acknowledged the challenge at a press conference, stating that combating AI-driven disinformation would be one of the biggest hurdles in this election. “This is the age of AI,” he said. “I have been expressing concern about AI from the very beginning. It is going to be a major challenge for us.”

Experts note that nearly 80 million people in the country use the internet, and about 70 percent of them are active on social media. At the same time, most users are not accustomed to verifying information in the digital space. People tend to believe social media content without fact-checking, creating fertile ground for the rapid spread of misinformation. A single fake video, they warn, can easily influence millions. Without effective countermeasures, experts caution, the transparency and credibility of the election could be severely undermined. They emphasize the need for coordinated action by the government, the Election Commission, and political parties.

Cybersecurity analyst Tanvir Hasan Joha pointed out that the primary challenges in cyberspace are platforms like Facebook and YouTube. He said legal cooperation agreements must be signed with these platforms. “If such agreements are in place, Facebook authorities will provide information about those spreading disinformation to the government,” he said, adding that no such initiative has yet been taken.

DBTech/MUM/EH/OR