Broadband Battles: Balancing Costs, Quality, and Consumer Concerns

On January 22, the National Board of Revenue (NBR) withdrew the newly imposed 10% supplementary duty on broadband services following objections from service providers and consumers. Seizing the opportunity, the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) has submitted a proposal to the Ministry of Finance to reduce broadband internet prices for consumers by up to 20%.

If approved, the cost of a 5 Mbps broadband connection—currently priced at BDT 500—will drop to BDT 400.

However, internet service providers (ISPs) claim they were not consulted on the matter. They argue that without a price reduction at the Nationwide Telecommunication Transmission Network (NTTN) and International Internet Gateway (IIG) levels, the initiative could backfire. ISPs fear such a move may compromise service quality and boost illegal operators’ activities.

“What’s the point of cheaper internet if its quality is poor?” many consumers question, reflecting concerns about the potential trade-off between affordability and service reliability.

Meanwhile, the rationale behind the proposed price cut remains unclear, as broadband internet in Bangladesh is already relatively cheaper compared to neighboring countries like India, Pakistan, and Nepal.

Comparative Analysis of Broadband Internet Prices in Neighboring Countries

The cost of broadband internet in Pakistan varies based on the provider and speed. According to information from the websites of local operators like PTCL, Nayatel, Jazz, and Wateen, monthly broadband expenses range between PKR 1,500 and 4,000. For instance, a 1 Mbps package with a 10 GB download limit is available for PKR 599. A 2 Mbps package with a 15 GB limit costs PKR 750, while an unlimited 100 Mbps connection is offered at PKR 1,000.

In India, broadband internet is significantly cheaper compared to Pakistan. Market analysis reveals that the monthly cost of broadband internet starts at INR 499 for a minimum speed of 4 Mbps. Typically, broadband packages range from INR 500 to 1,500 or more. Providers like Jio and Hathway offer various plans that include speeds between 100 Mbps and 1 Gbps. For example, BSNL provides 30 Mbps internet with a 1,400 GB data cap for INR 399, while Jio offers unlimited packages such as 30 Mbps for INR 399, 100 Mbps for INR 699, and 150 Mbps for INR 999.

Bhutan, on the other hand, has comparatively higher broadband internet costs in South Asia. Leading providers like Bhutan Broadcasting Service and DrukNet offer packages priced between BTN 1,000 and 3,000 per month. These plans typically include speeds of 20 Mbps, 50 Mbps, and 100 Mbps.

In Nepal, broadband internet is priced between NPR 1,000 and 4,000 or higher, depending on the speed and quality. Providers such as Nepal Telecom, Ncell, WorldLink, and SmartLink offer competitive packages. For instance, 200 Mbps internet is available for NPR 1,300, and 250 Mbps costs NPR 1,550, excluding VAT. Favorable government policies and fewer service layers have contributed to the higher speeds and better quality in Nepal.

Market Experts Warn Against Setting Broadband Prices Without Consultation

Market analysts believe that unilaterally setting broadband prices without consulting service providers will not be sustainable and may create market disruption. Referring to BTRC’s earlier “U-turn” on unlimited mobile data packages, some have questioned whether the regulatory body is heading toward becoming a “fascist commission.”

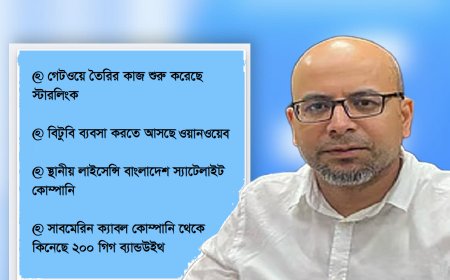

Commenting on the matter, AKM Fahim Mashroor, CEO of the popular job portal BDJobs, former BASIS president, and a member of the task force for equitable and sustainable development strategies, stated, “Broadband prices in Bangladesh are not high; mobile data is where the issue lies. The current 20% supplementary duty on mobile data should be lifted. It can remain for voice services. ISPs have no room to lower prices here. To reduce costs for end users, drastic price cuts are needed at the NTTN and IIG levels. Without restructuring the overall cost structure, reducing broadband costs will not be possible, nor will digital inequality be addressed. Mobile internet prices must be reduced, but that too is challenging since the government takes 60% of the revenue.”

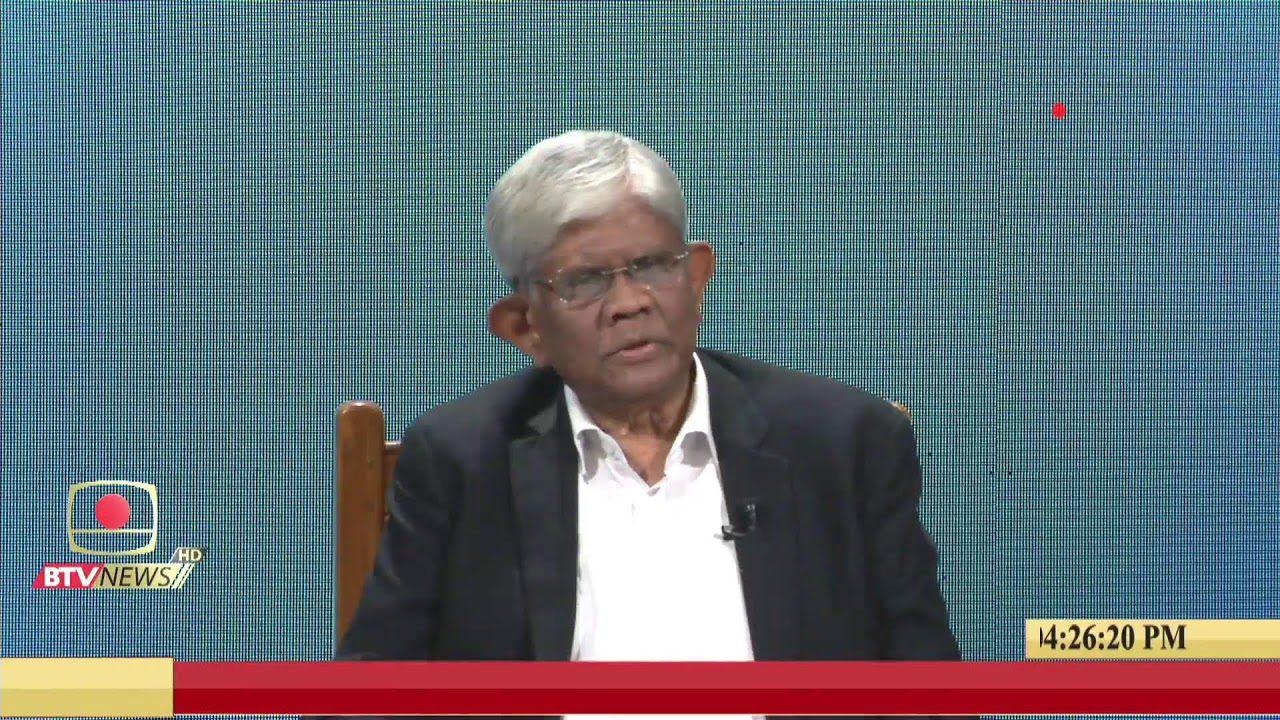

Mohiuddin Ahmed, President of the Mobile Subscriber Association, expressed concerns about the quality of broadband services amidst price reduction efforts.

He stated, “In many markets, broadband lines are available for as low as 400 BDT, but the quality is not up to the mark. We want quality internet. The way BTRC is approaching broadband price reduction seems authoritarian. This is an impulsive decision, and in the end, nothing significant will be achieved.”

Echoing similar concerns, Fida Haq, Coordinator of Voice for Reform, stated, “The foremost priority for broadband internet should be ensuring service quality. If prices are reduced at the customer level without lowering costs at the NTTC and IIG levels, service quality will inevitably deteriorate. Additionally, I believe the price of mobile internet also needs to be reduced.”

Didarul Islam Bhuiyan, Coordinator of Statecraft, emphasized the need for a structured approach, saying, “Reducing internet prices requires a roadmap. Middlemen must be identified and addressed. However, instead of doing so, compromises are being made on quality.

This isn’t driven by genuine intentions but by ill-intentions. It’s a deceptive move, a demonstration of BTRC’s activism. This reeks of dishonesty and seems like an effort to sabotage the entire process, setting a disastrous precedent for future governments. They are repeating the same mistakes as their predecessors.”

When asked about preparations regarding BTRC’s initiative to lower internet prices, Emdadul Haque, President of the Internet Service Providers Association of Bangladesh (ISPAB), stated, “After resolving the issue of the 10% tax on internet services, we are hearing such news. However, as far as I know, there has been no market research or discussion on this. BTRC does have the authority to impose such decisions without consultation. The ‘One Country, One Rate’ initiative was also implemented in a similar manner. This led to increased influence of unlicensed operators and a decline in internet quality. Neither customers nor the government benefited from this. In fact, compliant companies were forced to leave the business.”

When asked why, he broke down the costs, explaining, “In a 5 Mbps connection with a package costing 500 BDT, there’s no profit. The operational cost for shared lines (1:5 ratio) in a 5 Mbps package is 398 BDT. Of the 500 BDT, 60%—amounting to 238 BDT—goes to the government. Another 60 BDT is paid to the NTTC. Whatever little business is generated through corporate clients barely keeps us afloat. Even though we do not profit, the combined layers of the sector contribute 320 crore BDT monthly to the state treasury. Broadband internet significantly accelerates productivity. Increasing pressure on this sector will indirectly burden the overall economy. This is not difficult to understand.

That’s why I must say—this is cheap politics, much like that of the previous government. ‘One Country, One Rate’ was forced upon us then, and we opposed it. We oppose it now as well. What we want is a free-market system where competition determines pricing. With 3,000 companies in the market, they are fully capable of determining the best rates in an open market.”

Echoing similar concerns, ISPAB General Secretary Nazmul Karim Bhuiyan added, “I am not aware of any country that offers broadband services at a lower cost than ours. Yet, we are burdened with narrowband connections below 20 Mbps. We are struggling to deliver local data to remote areas under pressure from the NTTC. If the goal is truly to reduce internet prices, then the ‘One Country, One Rate’ policy should also be implemented at the NTTC and IIG levels. Additionally, the discrimination in bandwidth procurement between mobile operators and ISPs must be eliminated. Otherwise, this will add another layer of digital suffering for the end users.

“Fixing prices in any form is a mockery of free-market economics,” he continued. “It disrupts the process where consumers seek the best service at the lowest cost in a competitive market.”

Challenges in Internet Pricing

Discussions with industry insiders reveal that BTRC has set prices for IIG-level bandwidth at 365 BDT per Mbps and bandwidth transport costs at 25 BDT per Mbps for ISPs. Despite this, IIGs, in an attempt to maintain market equilibrium, proposed reducing the rate to 200 BDT per Mbps but received no response. To stay competitive, many IIGs are already offering bandwidth at 180 BDT per Mbps.

At the NTTC level, the cost could potentially drop below 10 BDT per Mbps, but the BTRC-enforced rate of 25 BDT per Mbps prevents such a reduction. As a result, internet service providers (ISPs) are facing increasing pressure at the customer level.

ISPs have stated, “Running overhead lines to every household to provide connections is a significant investment at risk. Under these circumstances, reducing prices and expanding connections to remote areas have become nearly impossible, leaving us backed into a corner.”